Preface And Klamath River

Basins

From 50 Years On The

Klamath

by John C. Boyle

In the records of trappers, explorers and trail blazers, many

references were

made to the lakes, rivers and mountain streams in the Klamath

country. Most of the

settlers who followed these men were headed for the

Sacramento

or the

Willamette

Valley

or the mining districts in between. Only a few who had no quarrel

with the

Indians remained and took up homesteads or purchased swamp and

overflowed land from

the government.

The country was wide open for stock raising with plenty of free

pasture and range lands.

In some localities, settlers obtained large holdings, and claimed

lands best suited for their

purposes. Streams were diverted for irrigation, dikes were built

to protect lands from overflow

and means sought to get rid of surplus waters. Each settler had

his own idea about water,

often different from that of his neighbor, which lead to

misunderstandings, ill feelings, and lawsuits.

The citizens in the Klamath communities realized that water was

the greatest asset of the

area. When efforts were made to divert it elsewhere, they

unanimously maintained the

position that all the water was needed for the ultimate

development of the basin of its origin.

At the turn of the century when irrigation and power engineers

visited the area, they generally

agreed that if properly conserved and utilized, there was enough

water to supply every need

which might locate in the

Klamath

Basin

. This conclusion still holds true in 1976.

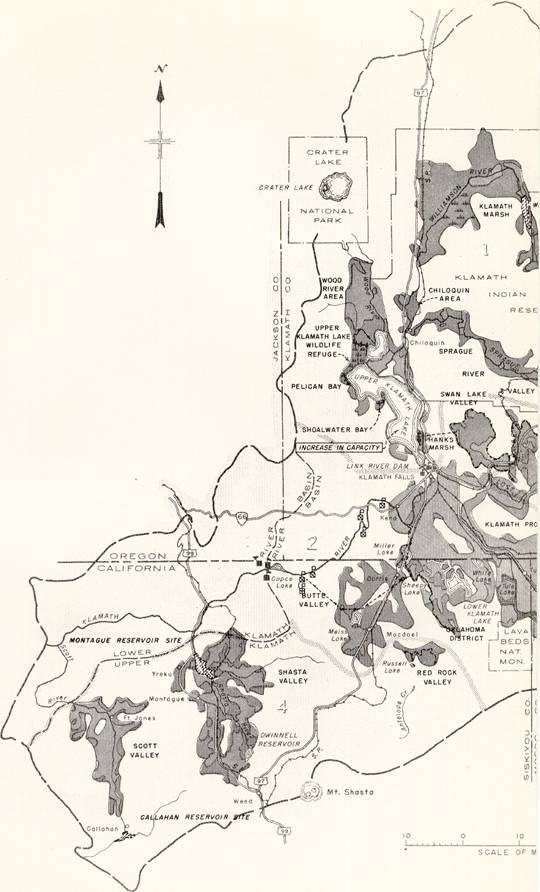

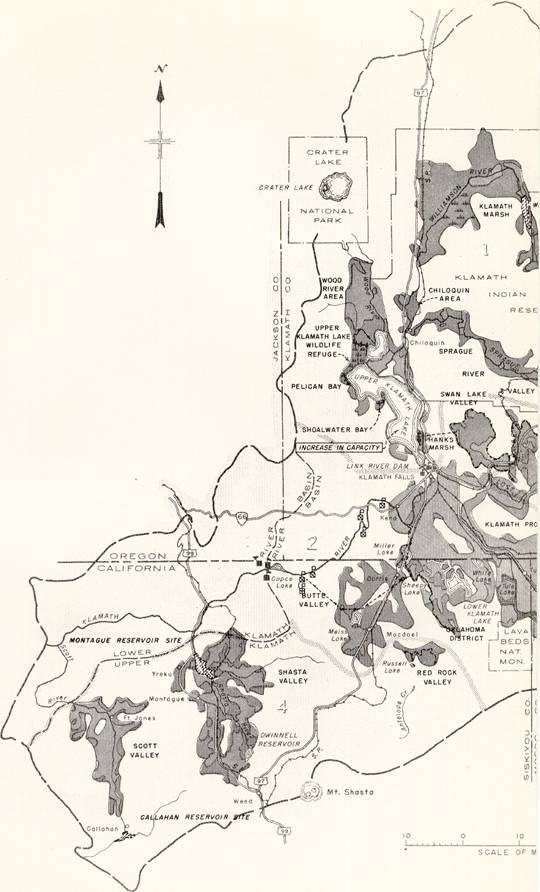

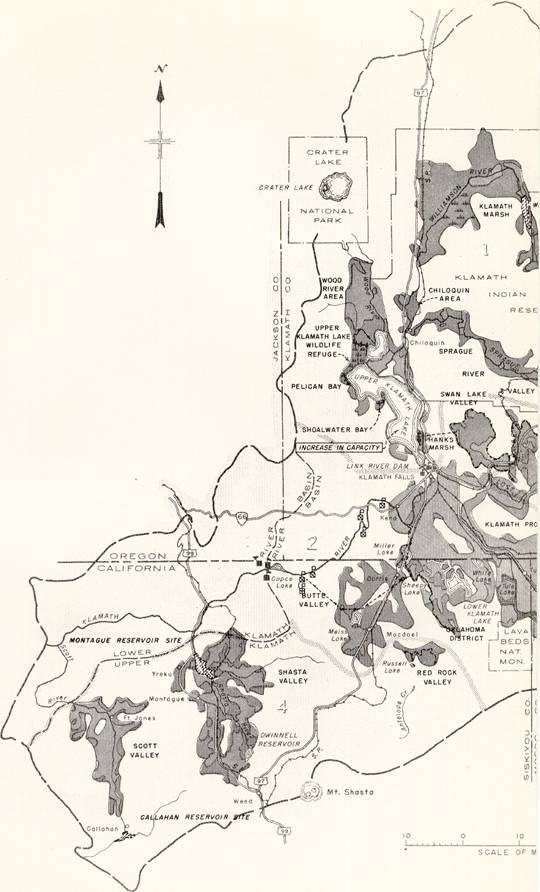

KLAMATH RIVER BASINS

As

Klamath River

is an interstate stream, the question of water rights in

Oregon

and

California

and the use of water in each state has been an unsettled

matter for many years.

Oregon

had put to beneficial use water for irrigation long before

the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation started its Klamath Irrigation project in 1905.

California

had used water beneficially for mining, irrigation, and

development of power from the days of early settlement in

Northern California

. The total drainage area, estimated at 15,500 square miles

not including the Trinity River basin, supplied sufficient water for both states

if put to beneficial use within its basins.

The

Klamath River as it left the irrigated areas above Keno,

Oregon

, dropped about 4100 feet in almost 250 miles into the

Pacific Ocean . Throughout this distance it flowed

primarily into a canyon with steep narrow sides, with very little flow through

lands, which were or might be irrigated.

Power sites were numerous

between Keno and the

Pacific Ocean . The most attractive of these were in the

first fifty miles of the river below Keno where the fall in the river is about

2500 feet, with lake regulation and storage reservoirs at the source.

In-flow streams like Willow Creek, Shasta River, and

Scott River, all tributary to Klamath, had areas of agriculture land, which

needed supplemental irrigation water, and looked to the Klamath as the principal

source of supply.

The Bureau of Reclamation, the

Oregon

and California Klamath River Compact Commission, and the California Oregon Power

Company (Copco) each divided the

Klamath

River basin

into two parts, the

Upper

Basin

and the

Lower

Basin

.

Upper

Klamath

River Basin

The Bureau of Reclamation defined the

Upper

Klamath

Basin

as an area drained by the

Klamath River and all its tributaries above Copco No.2.

This was done for the purpose of including any diversion of water into

Butte

Valley

and

Shasta

Valley

for irrigation in those valleys.

The

Oregon

and California Klamath River Compact Commission designated

the

Upper

Klamath

River basin

as that portion of the basin tributary to the

Klamath River

above the Oregon-California state line. Portions of this area

in

California

included

Butte

Valley

and

Red

Rock

Valley

drainage, which flowed northerly and was used for irrigation

in

Oregon

. Some of the arid lands in

California

receive irrigation water from tributaries of the

Klamath River

in

Oregon

. Each state retains its sovereignty.

The California Oregon Power Company expected to develop all

the power resources of the

Upper

Klamath

River basin

to and including

Iron Gate ,

so they determined the boundaries of the

Upper

Klamath

River basin

as all the drainage areas above

Iron Gate .

In using the

Upper Klamath Lake for storage and creating additional

reservoirs in the

Upper

Basin

, it was generally agreed by all interested agencies that the use for irrigation

within the

Upper

Klamath

Basin

had a priority over the use for power purposes. And it was agreed that all

drainage flows within the

Upper

Klamath

Basin

would be returned to the

Klamath River above Keno. The only diversions permitted

to go outside its basin would be the diversions from

Four

Mile

Lake

to the Medford Irrigation District and the diversion of

Jenny

Creek

to the Talent irrigation District on

Greenspring

Mountain

.

Lower Klamath

River Basin

. The

Lower Klamath

River Basin

included the

Klamath River and all its tributaries between

Iron Gate and its confluence with the

Pacific Ocean . This part of the basin included

Shasta

Valley

and

Scott

Valley

as the areas most likely to be developed by irrigation. The balance of the area

needed very little water for the lands, which may be irrigated, and, because of

its canyon walls and rough terrain, it had been established as a fish and, game

district by legislative act of

California

,

December 17, 1924 . This

act also prohibited the construction of any dam or other artificial obstruction

below the confluence of the

Klamath River and the

Shasta

River

.

There are at least ten dam sites along the

Klamath River between Iron Gate Dam and the mouth of the

river, none of which were developed. They were chosen by different engineers at

different times and made the subject of exhaustive reports.

On a 1910 reconnaissance by Copco, only two of these were

mentioned as desirable, No. 1 at

Big Bend , four miles upstream from Happy Camp, and No.2

at

Ishi

Pishi

Falls

, just above the mouth of the

Salmon River .

The No. 1 site could be developed to produce about 30,000 KW

under a 100 foot head and about 45,000 KW under a 150 foot head, with a tunnel

length of about 3500 feet through the ridge which forms the big bend. The river

grade resulted in a fall of about 55 feet around

Big Bend . A small dam diverting the river to utilize

only the 55-foot drop could develop about 15,000KW.

A low level tunnel was proposed during the gold mining days to

unwater this five or six miles of river to placer mining but was never developed

because high head diversions from Thompson Creek and Indian Creek were better

used for hydraulic mining.

The flexibility offered in this project fit well into Copco's

plans to develop units of production which would serve the need of the

surrounding area. The transmission lines of the company were extended down the

Klamath River from Yreka to Grey Eagle mine and from Cave

Junction in

Illinois

Valley

to Happy Camp having in mind that a power plant at

Big Bend , in addition to serving the surrounding area,

would feed back to the company’s transmission system any surplus generation.

The site at

Ishi

Pishi

Falls

was probably the lowest cost per KW of any of the proposed developments on the

Klamath River below

Iron Gate . The foresight of Frank Langford and his

associates is commendable. He initiated water rights in 1908, obtained rights

of way and started extensive construction work. The amount of power he expected

to develop was flexible, starting with about 25,000 KW and ultimately developing

perhaps 200,000 KW, including waters from the

Salmon River . His problem was finding a market for his

power.

The territory immediately adjacent was sparsely

settled so he envisioned transmitting power to

Trinidad harbor for the production of aluminum, copper

and other electro-metals.

Application No.74 before the Federal Power Commission by the

Electro-Metals claimed rights from filings made in 1905.

The development of irrigation in

Scott

Valley

, like

Shasta

Valley

and others, was on a partial basis wherein certain areas were irrigated by

gravity or by pumping depending on the justified costs. Copco was interested in

the pumping developments as an outlet for sale of power. Therefore activity

engaged in studies and estimates for the benefit of those who requested such

service.

A review of many studies for

irrigating

Shasta

Valley

was made beginning with the James M. Davidson survey in 1892 and ending with the

California Department of Water Resources studies in 1963. There were found to be

37 engineering reports (see appendix B) together with comments, most of which

related to water for additional irrigation in Shasta Valley from Klamath River

as an outside source.

In all these studies, no one indicated that surplus waters of

Scott

Valley

could be used not only to irrigate an additional 30,000 acres in

Scott

Valley

, but could supply enough water to irrigate an additional 40,000 acres in

Shasta

Valley

.

Preliminary studies show that with a dam below the mouth of

Shackleford Creek, a pumping plant to pump water to a storage reservoir on

Moffatt Creek, and a tunnel to Yreka Creek all of these 70,000 acres could be

irrigated and supplemental water supplied to both valleys.

The average seasonal run off of

Scott

River

below Shackleford Creek for a 20-year period was about 460,000 acre feet and the

minimum run off of record 172,000 acre feet after diversion for lands now

irrigated.

Estimated

Scott

Valley

additional needs 60,000 acre-feet

Estimated

Shasta

Valley

additional needs 80,000 acre-feet

140,000 acre-feet

Excess average minimum run off above needs of both Valleys

-32,000 acre-feet.

UPPER

KLAMATH

RIVER BASIN

. Keno was the control point in the

Upper

Klamath

Basin

where the

Klamath River left the agricultural land and regulating

lakes and started down the canyon through the

Cascade Mountains on its course to the

Pacific Ocean . Keno has also been marked as the point of

division between irrigation and power, however diversions for irrigation were

proposed at points below Keno.

McCormick Site. On

February 20, 1906 an

agreement was made by the Reclamation Service with Thomas McCormick for purchase

of water rights and rights of way for building a cut in the Keno reef for

lowering the

Klamath River , possibly lowering

Lower Klamath

Lake

and providing a better discharge channel for waters from the proposed

Lost

River

diversion canal. The McCormick site was a strip 400 feet wide, 9000 feet long on

the south and west bank of the Klamath River, including power development

possibilities in this strip of 68 feet fall.

Deed executed

November 14, 1906

. Consideration $10,000.00

Bureau of Reclamation. During March and April 1906,

the Reclamation Service made preliminary surveys of the power possibilities

below Keno (McCormick Site) to

Beswick ,

California

. In the distance of about 28 miles it recorded an average drop of 51 feet per

mile and in some places 100 feet per mile. All public lands between Keno and

Klamathon ,

California

, bordering the river, were then withdrawn from public entry and reserved for

power development. No water filings were made by the Reclamation Service at that

time.

Southern Pacific Power Site. The property acquired

by the Southern Pacific Railroad Co. was purchased from it by Copco in 1921. I t

had a possible diversion dam site at the old crib dam and bridge on the Klamath

River six miles below Keno. The Southern Pacific had made preliminary

investigations and had excavated a bench along the north side of the river about

three quarters of a mile long, which could be used in connection with any power

development planned by that company.

It was assumed that this site together with

a site on the North Umpqua River and one on the Willamette River, were part of a

program to electrify the railroad from Redding, California to Eugene, Oregon if

and when such a railroad was built.

Southern Oregon Water Company. A proposed

development was that of the Southern Oregon Water Company who owned considerable

of the riparian lands between Keno and the California-Oregon state line, about

1300 acres.

The

incorporators of the Southern Oregon Water Company were mostly men connected

with the Long-Bell Lumber Company. The lands were subsequently transferred to

Weyerhaeuser. No developments of power were made although the lands controlled

some of the important power sites.

Long-Bell Lumber Company was asked whether or not it intended to

develop power on its holdings. It had thought at one time that it might be

economical for Long-Bell and Weyerhaeuser jointly to develop power and use it in

their mills and manufacturing plants when they built them in

Klamath Falls

, but were since convinced that they could buy power cheaper than they could

develop it. Negotiations resulted in the purchase of all these holdings by Copco.

State of

Oregon

. On

August 28, 1913 a withdrawal

of 1000-second feet from appropriation of the waters of the

Klamath River was made on behalf of the State of

Oregon

to be used for power development. Chapter 87, Laws of

Oregon

, 1913. Legal opinion pointed out that:

"In view of Chapter 228, General Laws of

Oregon

, 1905, and the action taken by the

United States

in pursuance thereto, it was questionable whether or not the state could issue

any permits for the appropriation of any of the waters within the

Klamath River and

Lake

Basins

.

"If the state may issue permits, there is a legal question as to

the effect of the state's withdrawal."

Keno Power Company. The Keno Power Company's first

plant was put into operation in 1912.

On

April 4, 1917

the Keno Power Company asked the city of

Klamath Falls

for a franchise and grant for 25 years to supply for all

purposes, electricity within the city limits as then established and within any

future extended boundaries.

Copco asked for and obtained an injunction against granting such

a franchise. This caused a battle between the two power companies.

Keno Power's power plant was being used to supply power and

lights to a few farmers in the neighborhood of Keno, but it had no lines within

the town of

Klamath Falls

and no line leading to it.

Copco brought suit in the Federal court on the basis that for a

long time it had been serving

Klamath Falls

and was under Public Service Commission of Oregon, which had power to determine

the convenience and necessity of allowing a second utility to invade the field

of one already in an area.

Under date of

June 15, 1917 , Keno Power

Company gave the Oregon Klamath Record a story of its activities:

" ...we have made extensions totaling about ten miles of

transmission lines serving new pumping station…100 H.P. The Pine Grove extension

will serve a 75 HP plant and intend to serve all farmers above the reclamation

canal. ...We have recently ordered a new turbine that will take care of all

needs of Klamath county for several years to come."

The result of all the argument between Keno Power Company and

Copco was confusion among the citizens of the community and the development of

personal bitterness among the officers of both companies, which nearly developed

into physical violence.

During August 1919 Copco made a study of the

Klamath River canyon between Keno and the mouth of

Spencer

Creek

including the power plant of the Keno Power Company. A fall of about 260 feet

could be developed to produce about 48,000 KW.

Some riparian lands had already been acquired by Copco. All

property ownerships were determined and other needed riparian lands surveyed.

The power plants and distribution lines of Keno Power Company

were acquired by Copco on

April 1, 1920 . They were

operated as a separate utility until

January 1, 1927 when they

were merged into the Copco system.

In an

August 8, 1919 reconnaissance

report on the

Klamath River at Keno the following data was included:

Drop in Kerns plant about 30 feet.

Dam about 400 feet long, rock cribs filled with loose rock and

timber of all kinds. Two-inch planks placed vertically against upstream face of

timber and rocks.

Canal 300 feet long, 30 feet wide at water surface, lined for 125

feet at lower end with concrete.

Old power house No. 1 (125 KW) no longer used.

Penstock to No. 2 power house made of concrete with wooden gates

in concrete guides.

New power house No. 2 in fair shape, 360 KW generator. 2300 V,

200 RPM.

Line Voltage 10,000.

Water rights of

Keno Power Company:

July 15, 1911

55 Sec ft

Jan. 20, 1914 200 Sec ft

June 11,1914 550 Sec ft

Total 805 Sec ft

An additional 750 KW unit No.3 was moved from the Gold Ray Power

Plant on

Rogue River and installed in 1921 by Copco.

The Klamath Irrigation District on

August 8, 1929 filed an

application with the State Engineer to appropriate 2000-second feet of water

from

Klamath River to develop 22,600 horsepower (McCormick

power site). Upon receipt of the application, the Attorney General issued an

opinion dated September 3,1929 that unless it was determined by the State

Engineer that there was no conflict with the water rights of the United States,

that the application might be approved, but whatever rights might be allowed the

district, such would be junior to those of the government. No further action was

taken by the State Engineer. The application was authorized to be cancelled by

the District.

When this decision was known,

Copco presented its claim for water rights and the State Engineer, on advice of

the Attorney General, held that the power company had the same rights to

appropriate water as the Irrigation District, providing that a waiver of power

rights be made in favor of irrigation use. Such a waiver was executed by Copco

and filed with the State Engineer's office. No approval was received.

U. S. Senate Bill S-3556, introduced at the request of the

Klamath Irrigation District, was discussed on

December 16, 1930 and

January 19, 1931 before the

Committee on

Public

Lands

and Survey. This bill "authorized the sale of a certain tract of land in the

state of

Oregon

to the Klamath Irrigation District." This McCormick site bill was never passed.

The Bureau of Reclamation advertised the McCormick

site for sale on

January 18, 1927 . Many

protests were filed against the sale, so on the date of sale Copco made public a

statement " ...that it was not interested in making a bid for purchase of the

McCormick power site as it was not an economical site on which to build compared

to some of the lower sites." However, if any bids were received Copco would

withdraw this statement.

Buck

Lake

. During February 1914 investigation was made of

Buck

Lake

as a source of water supply for irrigation in

Rogue River

Valley

. Discharge measurements were made with a topographic survey of the drainage

area. Elevation of the lake at about 5000 feet above sea level and a reservoir

of 30,000 acre feet capacity could be created.

A tunnel of

10,000 feet, and a canal of about 25 miles in length would take the water from

Buck Lake to the Dead Indian summit where about 25,000 acre feet of water could

be delivered to the head of Walker Creek Rogue River side.

Buck

Lake

was acquired by Copco in 1924 and was considered of value as a regulated water

supply for the

Klamath River below Keno and a prospective gravity supply

for the

Klamath Falls

domestic water system, 26 miles distant.

Shasta Valley Irrigation District. On

August 20, 1920 Roy E.

Swigart made application to appropriate 1500-second feet of water to be diverted

at Keno for the Klamath-Shasta Valley Irrigation project.

On

September 10, 1920

another filing was made for 4000-second feet to be diverted

at Keno and all unappropriated and surplus water for irrigation in

Sacramento

Valley

and for power purposes,

On

December 24, 1920

application was made by Roy E. Swigert to appropriate 160,000 acre feet of water

to be stored in

Lower Klamath

Lake

for the proposed Klamath-Shasta Valley Irrigation project,

On December 30, 1920 headlines in Sacramento read that Shasta

Valley's Narboe said, "Briefly the plan is to irrigate Shasta Valley with stored

water from Klamath Lake without interfering with the agricultural needs of any

part of the Klamath drainage basin and without reducing the power possibilities

of the Klamath River, W, W, Watson was the engineer for District 11,"

On January 14, 1921 a meeting was called at Montague, California

for the purpose of acquainting everyone with the Shasta Valley-Klamath Project,

Hearings had been held before Secretary of Interior Payne at which Dr, Elwood

Meade and Director Davis attended and they were to report that if the project

was found feasible they would take up the question of water supply and Upper

Klamath Lake storage, as they were the best authority to adjust the interest of

irrigation and power.

Interest lagged and little if anything further was done for

another ten years.

Sacramento

Valley

Farmers.

September 20, 1930 headlines

read, "

Sacramento

Valley

farmers are endeavoring to get Klamath Water." Filing was made on 4000 second

feet from

Klamath River to develop power and furnish irrigation

water for entire state-a $15,000,000 project. Representatives of Sacramento

Valley Irrigation District encouraged by the Col. E. B. Marshall plan said the

water could be taken down the

Sacramento River all the way to southern

California

. "

City of

Klamath Falls

. The City of

Klamath Falls

made application

July 24, 1933 , by Mayor

Willis E. Mahoney to appropriate water to develop power for a municipal plant in

the NE 1/4 of Sec. 31, T39S R7 E WM. The amount of power was not stated but 1500

second feet of water was specified. As Mahoney was advised that he would have to

bring a suit against the State of

Oregon

to get a permit to use water, the application was withdrawn.