TESTIMONY OF DAVID A. VOGEL

Before the House Committee on Resources

Oversight Field Hearing on:

Water Management and Endangered Species Issues in the Klamath Basin

June 16, 2001

Mr. Chairman and members of the Committee, thank you for the opportunity to testify at this

important hearing. My name is David Vogel. I am a fisheries scientist who has worked in this

discipline for the past 26 years. I earned a Master of Science degree in Natural Resources

(Fisheries) from the University of Michigan in 1979 and a Bachelor of Science degree in Biology

from Bowling Green State University in 1974. I previously worked in the Fishery Research and

Fishery Resources Divisions of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) for 14 years and the

National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) for one year. During my tenure with the federal

government, I received numerous superior and outstanding achievement awards and

commendations, including Fisheries Management Biologist of the Year Award for six western

states. For the last 10 years I have worked as a consulting fisheries scientist on a variety of

projects on behalf of federal, state, and county governments, Indian tribes, and numerous other

public and private groups. During the past decade, I have advised the Klamath Water Users

Association (KWUA) on Klamath River basin fishery resource issues. I was the principal author

of the 1993 “Initial Ecosystem Restoration Plan for the Upper Klamath River Basin” and was

one of the primary contributing authors to the Upper Basin Amendment to the Klamath River

fishery restoration program. I was a principal contributor of information for the 1992 Biological

Assessment on Long-Term Operations of the Klamath Project. More recently, I was a

contributor to technical portions of the March 2001 document, “Protecting the Beneficial Uses of

Waters of Upper Klamath Lake: A Plan to Accelerate Recovery of the Lost River and Shortnose

Suckers”. This plan was also authored by Dr. Alex Horne and I have attached his March 21,

2001 testimony before the Senate Subcommittee on Water and Power. I have performed

research projects on coho salmon and the endangered suckers, as well as many other species.

Today, I am providing your Committee with important information concerning the science, or

more aptly stated, lack of rigorous science, behind the artificially created regulatory crisis that

has been imposed on the Upper Klamath basin. These topics relate to the sucker fish, which the

USFWS has focused on to regulate higher-than-normal lake elevations in Upper Klamath Lake,

and coho salmon, which NMFS has focused on to demand higher-than-normal flows below Iron

Gate Dam on the Klamath River. And lastly, I am providing your Committee with

recommendations to avoid the regulatory crisis that has been created in the Klamath Basin.

2

Decision-Making Process

In my entire professional career, I have never been involved in a decision-making process that

was as closed, segregated, and poor as we now have in the Klamath basin. The constructive

science-based processes I have been involved in elsewhere have involved an honest and open

dialogue among people having scientific expertise. Hypotheses are developed, then rigorously

tested against empirical evidence.

None of those elements of good science characterize the decision-making process for the

Klamath Project. At one time, several years ago, the agencies would interact with all interests

who had expertise or a stake in the decisions. Recently, my role has been to receive completed

analyses (usually without supporting data) and mail in comments. Often, the timeline is such

that it is virtually impossible to comment and certainly impossible for the agencies to consider

the comments objectively and meaningfully. The overriding sense I have is that the goal is to

dismiss what we have to offer. A scientist that I work with has had the experience of being

invited to a technical meeting, then literally turned away. Additionally, we have been invited to

attend recent meetings related to downstream flow studies, but our presence was requested at the

end of the process, after key assumptions had been developed.

I provide examples below of the kinds of information that have not, in my opinion, received

objective consideration or open discussion. I also include alternative actions and

recommendations.

Klamath Basin Suckers

Endangered Species Status

Disturbingly, I have learned from an extensive review of the relevant Administrative Record that

the information used by the USFWS to list the two sucker species as endangered in 1988 under

the Endangered Species Act (ESA) is now very much in question. The USFWS so selectively

reported the available information that it can only be considered a distorted view of information

available to the agency at that time. The dominant reason that the USFWS listed the species was

an apparent precipitous decline in both populations in the mid-1980s and the lack of successful

reproduction (recruitment) for 18 years. Documents selectively used by the Service to support

the listing portrayed an alarmist tone indicating that the species were on the brink of extinction.

Because of information in the Administrative Record and scientific data developed since the

listing, major questions are now posed calling into question the integrity of the original listing

decision.

3

Due to extensive research performed on the Lost River and shortnose sucker populations in

recent years, relative population abundance estimates are available for both species. Although

there are differences in the manner by which each estimate was computed and some estimates

have broad confidence intervals, the numbers represent the best available information that was

used by the USFWS to list and monitor the species. A comparison of estimates developed prior

to and after the listing demonstrates a remarkable change in the species’ status (Table 1). Recent

data demonstrates that the sucker populations exceeded the original estimates used to justify

listings by an order of magnitude.

It is now evident that either:

1) The estimates of the sucker populations in the 1980s were in error and did not, in fact,

demonstrate a precipitous decline (i.e., the populations were much larger than assumed), or

2) The estimates of the sucker populations in the 1980s were reasonably accurate and the suckers

have demonstrated an enormous boom in the period since the listing and no longer exhibit

“endangered” status.

Furthermore, in contrast to the lack of recruitment described in 1988, it is now very evident that

the Upper Klamath Lake sucker populations have experienced substantial recruitment in recent

years and also exhibit recruitment every year. Only three years after the sucker listing, it also

became apparent that the assumptions concerning the status of shortnose suckers and Lost River

suckers in the Lost River/Clear Lake watershed were in error. Surveys performed just after the

sucker listing found substantial populations of suckers in Clear Lake (reported as "common")

exhibiting a biologically desirable diverse age distribution. Within California, the USFWS

surveyors considered populations of both species as "relatively abundant, particularly shortnose,

and exist in mixed age populations, indicating successful reproduction". Recent population

estimates for suckers in the Lost River/Clear Lake watershed indicate their populations are

substantial, and that hybridization is no longer considered as “rampant” as portrayed by the

USFWS in 1988. Tens of thousands of shortnose suckers, exhibiting good recruitment are now

known to exist in Gerber Reservoir. In 1994 the Clear Lake populations of Lost River suckers

and shortnose suckers were estimated at 22,000 and 70,000, respectively, with both populations

increasing in recent years exhibiting good recruitment and a diverse age distribution (Buettner

1999). Unlike the information provided by the USFWS in the 1988 ESA listing, it is now

obvious that the species' habitats were sufficiently good to provide suitable conditions for these

populations. Additionally, the geographic range in which the suckers are found in the watershed

is now known to be much larger than believed at the time of listing. The shortnose populations

in the lower Klamath River reservoirs (J.C. Boyle, Copco, and Iron Gate), previously believed to

be small or essentially non-existent at the time of the listing, are more abundant and widespread

than assumed in 1988 (Markle et al. 1999).

4

In summary, although the species had obviously declined from their historic population levels in

the early to mid-1900s, the surmised status of the species was not as severe as assumed in the

mid- to late-1980s. The two fish species presently exhibit far greater numbers, over a much

larger geographic range, and with greater recruitment than assumed more than a decade ago.

“Remnant” populations postulated in 1988 are now known to be abundant. “Severe”

hybridization among the species assumed in 1988 is now known not to be as problematic. In the

mid-1990s, Upper Klamath Lake sucker populations were found to exist on an order of

magnitude greater than believed in the mid-1980s. And it is now clear that widespread

recruitment of both species regularly occurs.

This all leads to an important, albeit an awkward, question for the USFWS and is one that the

agency cannot, or will not, answer. Which assumption is correct: that posed by the agency in

1988 or that of the present day? The species were either inappropriately listed as endangered

because of incorrect or incomplete information or the species have rebounded to such a great

extent that the fish no longer warrant the “endangered” status.

Upper Klamath Lake Elevations

I believe the USFWS’s recent Biological Opinion on the Operations of the Klamath Project has

artificially created a regulatory crisis that did not have to occur. This circumstance was caused

by the USFWS’s focus on Upper Klamath Lake elevations and is a major step in the wrong

direction for practical natural resource management. The USFWS rationale for imposing high

reservoir levels ranges from keeping the levels high early in the season to allow sucker spawning

access to one small lakeshore spring, to keeping the lake high for presumed water quality

improvements. This measure of artificially maintaining higher-than-historical lake elevations is

likely to be detrimental, not beneficial, for sucker populations. The data do not show a

relationship between lake elevations and sucker populations, and to maintain higher-than-normal

lake elevations can promote fish kills in water bodies such as Upper Klamath Lake.

During the mid-1990s, I predicted that fish kills could occur if the Upper Klamath Lake

elevations were maintained at higher-than-historical levels. Subsequently, those fish kills did

occur. The USFWS recent Biological Opinion dismissed or ignored the biological lessons from

fish kills that occurred in 1971, 1986, 1995, 1996, and 1997 and, instead, selectively reported

only information to support the agency’s concept of higher lake levels. All the empirical

evidence and material demonstrate that huge fish kills have occurred when Upper Klamath Lake

was near average or above average elevations, but not at low elevations (Figure 1). This is not

an opinion but a fact extensively documented in the Administrative Record and subsequently

ignored by the USFWS.

5

A good indicator that Upper Klamath Lake elevations do not create a “population-limiting

factor” for the suckers is a comparison of historical seasonal lake elevations with sucker year

class strength that may or may not result from those lake elevations. Sucker year class strengths

for some years are now available because suckers killed during die-offs in 1995, 1996, and 1997

were examined to determine the age of the fish. This allows a determination of the year the fish

were hatched and, because sufficient numbers of fish were collected, the relative “strength” of

one year class compared to other years. Using this new analysis of the best available scientific

information, it is evident the sucker populations do not experience a population-limiting

condition from lower lake elevations as incorrectly postulated by the USFWS. In fact, one of the

strongest year classes of suckers occurred during a drought year in 1991 when lake levels were

lower than average. These data demonstrate that there are no clear relationships between Upper

Klamath Lake elevations and sucker year-class strength. Additionally, the data now demonstrate

that the two species did not suffer “total year-class failures” during the drought years in the late

1980s and early 1990s as was commonly speculated at that time. It is particularly noteworthy

that the strong 1991 class of suckers experienced extremely low lake elevations during the severe

drought of 1992 but nevertheless remained the dominant year class observed in 1995, 1996, and

1997. Also, based on the age structure of suckers determined from the 1997 fish kill, it was

readily apparent that many older-aged suckers were in the population; from the early 1990s until

1997, it had been surmised that the age structure of the sucker populations were almost entirely

younger fish. This new evidence indicates that environmental conditions resulting from the

drought, including low lake elevations, did not have the adverse impacts on the sucker

populations assumed by the USFWS. The USFWS Biological Opinion notably ignored

extremely relevant scientific data and information that was contrary to the agency’s premise in

the Biological Opinion. The USFWS failed to point out empirical evidence the agency could

have provided in the Biological Opinion which demonstrates that Upper Klamath Lake levels

lower than demanded in the Biological Opinion will not harm (and may actually benefit) the

sucker species.

Klamath Coho Salmon

In my opinion, the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) significantly and inappropriately

added to the regulatory crisis in the Klamath Basin by calling for higher-than-normal releases

from Iron Gate Dam under the auspices of protecting the coho salmon, a “threatened” species,

from extinction.

Primary Factors Affecting Coho are in the Tributaries, Not the Mainstem

Coho salmon, as a species, prefer smaller tributary habitats, as compared to larger mainstem

river habitats. This extremely important biological fact was not incorporated into the rationale

NMFS used to assess Klamath Project effects on coho. Fry and juvenile coho normally occupy

6

small shallow streams where there are more structurally complex habitats (e.g., woody debris)

than are found in larger, mainstream river systems; this fact is amply described in the scientific

literature. NMFS ignored the fact that proportionally and numerically only small numbers of fry

use the reach most affected by the Klamath Project as compared to the entire basin. NMFS has

notably failed to reconcile this critical piece of biologically relevant information. NMFS avoided

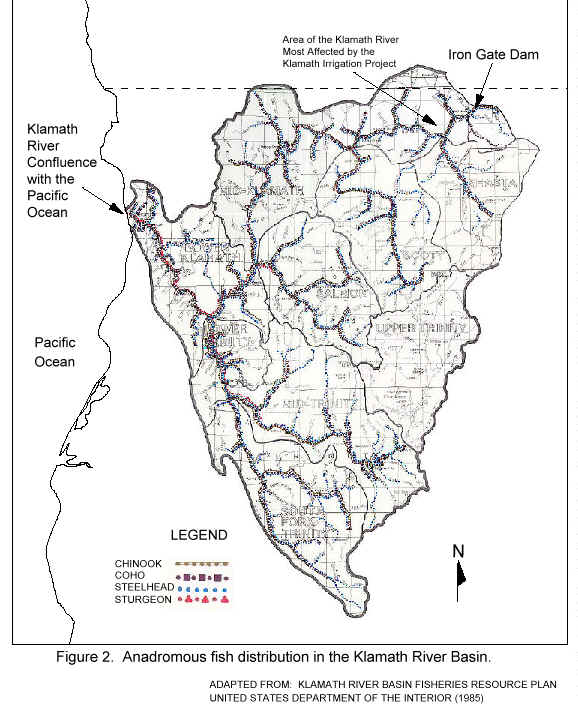

using an excellent source of information that would demonstrate this fact. A 1985 U.S.

Department of Interior document entitled: “Klamath River Basin: Fisheries Resource Plan”

thoroughly describes and graphically shows the distribution of coho in the Klamath Basin. That

voluminous, peer-reviewed document clearly demonstrates that the upper Klamath River, in

proportion to the entire Klamath River basin, is a geographically minor area of coho presence.

This fact is evident from the attached Figure 2 adapted from the Klamath River Basin

Restoration Plan. Instead of acknowledging this indisputable information, NMFS has singularly

focused on demanding dramatically increased, higher-than-historical flows from Iron Gate Dam

to “protect” coho from extinction. In so doing, NMFS has inappropriately suggested that coho

habitats should somehow be re-created in the large river channel downstream of Iron Gate Dam

to serve as a surrogate for the lost or degraded habitats in Klamath basin tributaries. This

misguided, scientifically deficient approach is unlikely to succeed.

I thoroughly reviewed thousands of pages of documents in detail to determine whether the

available scientific data and information suggest that the recent historical flow regime in the

mainstem Klamath River below Iron Gate has been a significant factor affecting Klamath River

fishery resources. These documents included scientific peer-reviewed literature, state and

federal agency documents and reports, and investigations encompassing many decades of

research on the Klamath River. This extensive review revealed that numerous factors other than

the recent historical mainstem flow regime at Iron Gate Dam are overwhelmingly documented to

have affected Klamath River fishery resources. There are many other documented factors that

have affected salmon runs in the Klamath River; I compiled a comprehensive listing of those

factors in March 1997 and provided that list to NMFS. None of the documents I have reviewed

provided any supporting scientific information or data suggesting that the historical mainstem

flow regime at Iron Gate Dam is a significant factor adversely affecting coho salmon. To the

contrary, the available information provides compelling evidence that other factors are far more

important in affecting fish populations than the recent historical Iron Gate Dam flow regime.

It is particularly noteworthy that the multi-million dollar, multi-agency Long-Range Plan for

restoring Klamath River anadromous fish (the principal document guiding salmon restoration in

the basin) addresses the issue of Iron Gate Dam releases and potential effects on salmonids in an

almost passing manner (Klamath River Basin Fisheries Task Force 1991). Nearly the entire

discussion in the Long-Range Plan on the topic of salmon production focuses on the tributaries

in the lower Basin. This is instructive because, despite all the efforts and research accomplished

to date on the Klamath River, no entity has developed any scientific data to support the premise

7

that specific Iron Gate releases over the past several decades has been a significant factor

limiting Klamath River salmonids.

Probably the strongest indicator demonstrating that the recent historical Iron Gate Dam flow

regime is not a primary factor affecting lower Klamath River fish is the response of the fish

populations. There are no apparent cause-and-effect relationships between historical flow levels

at Iron Gate Dam and resulting production of coho salmon. Clearly, there are other well

documented factors that have an influence on the Klamath River salmon runs than the flow

regime alone (e.g., harvest, hatchery production, tributary habitats).

The following are highly relevant facts ignored by NMFS in the agency’s Biological Opinion:

• Fry rearing habitat in the upper mainstem Klamath River is not as quantitatively or

qualitatively important to the species as is rearing habitat in the Klamath River tributaries.

• Numerically and proportionally, very small numbers of coho fry rear in the mainstem

downstream of Iron Gate Dam in the reach most influenced by the Klamath Project.

• The indirect effects of variable Iron Gate flow on adult coho populations in the Klamath

basin are minuscule when compared to other direct factors such as incidental ocean harvest

and other harvest of adult fish.

NMFS relied on a closed process to formulate the agency’s recommendations for Klamath River

instream flows. Individuals involved with this process purposefully excluded scientific experts

that could have provided meaningful input to the process. This exclusionary process is contrary

to scientific and procedural processes employed elsewhere in the United States, particularly in

California.

In summary, sound scientific bases for the NMFS Biological Opinion are lacking. NMFS relied

on an incorrectly applied and incomplete computer modeling exercise to support the agency’s

conclusions of the effects of the Klamath Project operations on coho. A close examination of the

NMFS Biological Opinion demonstrates that it does not empirically describe how Klamath

Project operations affect coho populations in the Klamath River basin. Instead, the agency’s

action resulted in too much warm water dumped in the wrong place at the wrong time and for all

the wrong reasons. The purported biological benefits to coho salmon will not be realized.

8

The Need for Alternatives using a Pro-Active, Adaptive Management Approach

Implement Meaningful Restoration Actions

New data and analyses indicate that regulatory measures and some research implemented over

the past decade, although perhaps well intended, misdirected resources away from other more

beneficial actions. Also, unfortunately, to the extent recovery or restoration efforts have been

undertaken over the past 13 years since the listing, they have not been effective. The USFWS

has contended that maintaining high reservoir elevations is the only feasible short-term measure

that can be implemented to benefit the sucker populations; this is incorrect. Alternatives are

available to benefit the species/ecosystem and have been presented to the agency. These

alternatives could have prevented the crisis we are in today.

There are fundamental changes that have occurred in Upper Klamath Lake that cannot be

ignored. As an example, the fact that non-native fish were introduced into the lake and are now

proliferating is a change that is absolute. Such changes have permanently altered the ecosystem.

Despite the emotional rhetoric one may hear about “Nature healing herself”, there is no turning

back to a so-called “pristine” ecosystem. These non-native fish prey on and compete with

suckers and will never be extirpated from the lake. However, there are numerous on-the-ground

actions that could be undertaken to improve the existing situation and provide greater flexibility

and balance for resource management. The Upper Klamath Basin is in a situation where millions

of dollars have been spent on “ecosystem restoration” (primarily land acquisition) under the

auspices of sucker recovery; unfortunately, the site-specific linkages to sucker recovery are

highly debatable and unclear. These benefits have not been forthcoming. It is time to take a new

approach.

Several recovery projects first identified in the early 1990s hold promise for increasing the

sucker populations. To this end, the KWUA recently developed a document entitled “Protecting

the Beneficial Uses of Waters of Upper Klamath Lake: A Plan to Accelerate Recovery of the Lost

River and Shortnose Suckers” (Plan) to promote timely implementation of biologically

innovative action-, and results-oriented restoration projects. This Plan was presented to the

Senate Subcommittee on Water and Power in March 2001. Some of the projects in the Plan are

embodied in the 1993 USFWS Sucker Recovery Plan, but have not been pursued. The Plan

focuses on implementation of specific actions to accelerate the recovery of the endangered

suckers while minimizing conflicts among competing uses for common resources. This Plan’s

use of cooperative efforts between local interests and those individuals and groups sharing

common goals is considered preferable to traditional fragmented plans which result in tragic

conflicts for limited resources we are seeing in the basin today. The Plan recommends actions

such as improving access of suckers in the Sprague River to physical and water quality

improvement projects in Upper Klamath Lake.

9

As with the suckers in the Upper Klamath Basin, there are viable alternatives and opportunities

to increase coho populations in the Lower Klamath Basin, particularly in the tributaries.

However, until NMFS changes its singular and misdirected focus on higher-than-historical flows

from Iron Gate Dam, restoration opportunities using the agency’s approach are unlikely to

succeed. Unfortunately, whatever the existing lower basin programs may have accomplished to

date, fishery restoration does not appear to be one of them. Although many millions of dollars

have been spent on the lower basin programs, benefits to fish have not been evident. A new

strategy of embracing a more holistic watershed approach and cooperative partnerships in the

tributaries, instead of the traditional adversarial approach is needed.

Implement Independent Peer Review

Many of the mistakes made by the USFWS and NMFS during this year could have been avoided

through a proper peer review of the agencies’ actions. It is imperative that the peer review not be

a facade of “like-minded” individuals or agencies promoting or protecting their policies or

positions. To prevent the flawed process that occurred this year, it will be necessary to ensure

that a peer review be performed by individuals without a vested interest in the suckers and coho

remaining listed species under the ESA; to do otherwise undermines the integrity of the scientific

process. For example, it is clearly inappropriate to have so-called peer review by some

stakeholders demanding water rights, including high lake levels. Likewise, researchers

dependent on the ESA controversy for funding may have a clear conflict with objective review.

Individuals that would use the threatened or endangered status as “leverage” to promote their

positions should also be excluded from the process. Additionally, the peer review should be a

“blind” review process to allow reviewers to be anonymous; this will ensure that “peer pressure”,

instead of peer review, does not occur. The peer review of the agencies’ Biological Opinions

should be performed outside the Departments of Interior and Commerce to avoid the problems

we have observed in the Klamath basin crisis. Data must be examined with clear, scientific

objectivity using widely accepted scientific principles. To be objective, agency policies and

positions do not belong in this scientific process. Good science will lead to good policy. And, if

the agencies are willing to do so, there is a great opportunity to accomplish restoration goals

without doing the kind of harm that is being experienced now.

10

References

Buettner, M. 1999. Status of Lost River and shortnose suckers. U.S. Bureau of Reclamation.

Presentation at the 1999 Klamath Basin Watershed Restoration and Research Conference.

CH2M Hill. 1985. Klamath River Basin fisheries resource plan. For U.S. Department of the

Interior.

Kier, William M., Associates. 1991. Long range plan for the Klamath River Basin conservation

area fishery restoration program. The Klamath River Basin Fisheries Task Force.

Markle, D., L. Grober-Dunsmoor, B. Hayes, and J. Kelly. 1999. Comparisons of habitats and

fish communities between Upper Klamath Lake and lower Klamath reservoirs. Abstract in The

Third Klamath Basin Watershed Restoration and Research Conference. March 1999.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1988. Final Rule: Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and

Plants; Determination of Endangered Status for the Shortnose Sucker and Lost River Sucker. 53

FR 27130-01.

1

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1988. Final Rule: Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Determination of Endangered Status for the shortnoseSucker and Lost River Sucker. 53 FR 27130-01.

2

ODFW estimates made by applying relative catch per unit of effort to previous population estimates (Fortune 1986).3

U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. 2001. Biological Assessment for the Klamath Project.4

“Population level – Trend and Number: From a reported great abundance prior to 1900, the species dwindled to an extremely low level during the 1950’s andearly 1960’s. Since about 1965 they have become more numerous. After a sampling trip through the spawning area in 1976, using a boat-mounted electric

shocker, E.C. Bond estimated there were several hundred to a thousand spawners. The Lost River population has been introgressed by Catostomus snyderi and

appears to have been lost.” Bond, C.E., Professor of Fisheries, Oregon State University. August 20, 1976. Letter to John Donaldson, Director, Oregon

Department of Fish and Wildlife nominating the shortnose sucker for inclusion on the Federal list of threatened species. 3 pages.

5

“The shortnose suckers, reported by Cope (1879) as abundant in Upper Klamath Lake, Oregon, now might be less plentiful. Carl E. Bond (pers. commun.,dated November 27, 1957) said he had difficulty obtaining specimens of

Chasmistes from Upper Klamath Lake.” Coots, Millard, 1965. Occurrences of the LostRiver sucker,

Deltistes luxatus (Cope), and shortnose sucker, Chasmistes brevirostris (Cope), in northern California. Calif. Fish and Game, 51(2): 68-7:68-73.6

“The shortnose sucker, Chasmistes brevirostris, which I was afraid no longer existed in Oregon, is still here, but very rare.” Bond, C.E. August 12, 1970.Letter to Clinton Lostetter, Coordinator, Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife regarding the Lost River sucker. 1 p.

7

Bond, C.E., Professor of Fisheries, Oregon State University. August 20, 1976. Letter to John Donaldson, Director, Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlifenominating the shortnose sucker for inclusion on the Federal list of threatened species. 3 pages.

8

Sucker Working Group minutes, December 3, 1987.